Working almost everyday with woven cloth makes you very aware of the type of edge that you have, ideally making kilts you want to have a finished edge at the bottom of the kilt, but one that isn’t actually hemmed. The traditional shuttle weaving produced a selvedge ( self-edge), a term that is widely and also a little inaccurately used today. A selvedge by actual definition is the clean edge formed when the shuttle on the loom goes back and forwards with a continuous and unbroken thread ; this method when carefully managed produces a beautifully pure edge with no added weight of change of feel, it is the most desired edge for kiltmakers.

Of course it isn’t always quite that simple, over the years kilting cloth has been produced on different types of looms and most weavers today use high speed looms which no longer can make a true selvedge. These looms can weave in a few hours what a traditional hand weaver would have woven in a week or more. With the change of loom there has been a change of fabric edge.

The most usual one for kilts is now called a tuck edge where one thread is woven at a time and then folded back upon itself for about a cm and then the next thread is introduced and forms the next line of cloth, working with a single length of thread is very much faster and looms use a variety of high speed methods for shooting the thread across including compressed air or even water, but the key thing is that a shuttle is no longer needed. This edge is slightly firmer and often a little more stable, but it has a little line of cut threads about 1 cm from the actual edge, these are not terribly noticeable depending on which side of the cloth is used. Most tartan weavers now use this edge for the majority of their production.

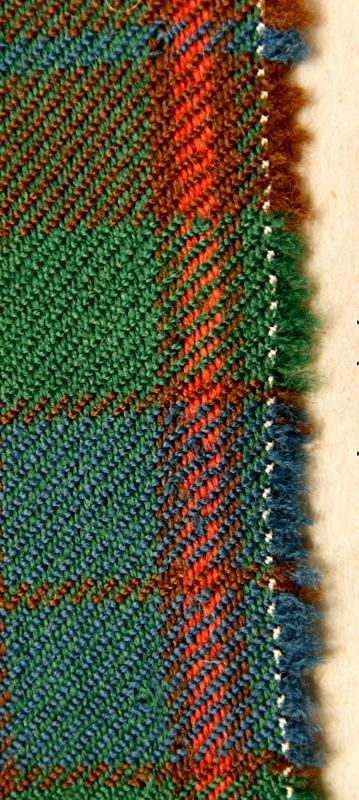

Another edge that is sometimes seen is a leno edge, which has a distinctive extra few twisted threads often white at the edge and a fringe from the uncut weft threads,this is the possibly the faster weaving method but it does mean that any kilt fabric will have to be hemmed. One excellent Scottish weaver has worked out how to have a selvedge on one side and a leno on the other, they use this on single width tartan and this means that a kiltmaker still has the chance to use a good edge at the bottom of the kilt, and the leno edge is cut off and used for the waistband, and hidden from view.

While a selvedge is the favourite it is not always the easiest to produce these days and is now more expensive with only a few weavers offering this. When it is well done it is excellent, but some weavers try it and fail miserably, this is an example of a rushed and imperfect selvedge, however with a lot of ironing, steam and pulling and stretching it can be made a little better, and if it wasn’t for a special order it would have been returned, a kiltmaker has enough to do without trying to fix a weaving problem. Often I’d rather have a tuck edge than having to spend time remedying a weaver’s problems.

Watching a weaver work is a wonderful experience, seeing the magic work of converting a mass of threads into a cloth is fascinating. Traditional looms for weaving tartan haven’t changed very much in hundreds of years, a strong wooden box like construction , but actually very simple, relying on the skill of the weaver and a flying shuttle ,it was the only way of producing any from of tartan until the beginning of the 19th century.

Mechanisation happened and the introduction of power looms made the mass production of tartan possible, dobby looms which followed around the 1850’s revolutionised the speed of weaving and the possibility of more complex designs.

It also meant that some weaving could be done at home or outbuildings which is largely how the Harris tweed industry came about, with a benevolent investor many looms were bought and the local community began to change what was already a low level cottage occupation into a world wide industry. The looms most associated with Harris tweed are the Hattersley single width looms many of which are still working nearly one hundred years later. They are wonderful work horses excellent for the substantial tweeds. These looms do produce a selvedge but realistically with the heavy yarn it’s not often usable without a hem for kilts. One edge will be smoothish and the other will have all the carried threads, but as the tweed is generally for pattern based clothing this presents no problems

One last little nugget; occasionally I see a thread that has been attached to a length of cloth this tells me that there is a fault of some sort, the thread is always at the edge ( this time a tuck edge) and the flaw will be roughly in line with it, when the cloth is rolled up it is easy to see how many threads to judge what sort of quality to expect, this is supposed to be the origin of the phrase “no strings attached” meaning that the cloth was good quality and that no extra work was needed to put it right!

If you are the Paul Henry who posts on Ravelry’s ‘Natural Dyeing’ group,

I just want to say how much I appreciate your comments, agree with what

you advise and follow your lead as a dyer!

I am, and you are very kind, thank you

Thank you, Mr. Henry, for your explanations and especially the photographs! I am looking to have a few kilts made and have seen these different types of selvedges mentioned for various tartans. While I understand what a kilted selvedge is and why it’s ideal, I’ve been wondering how the others look and what affect they may have on the quality and longevity of a kilt. I found several breakdowns and diagrams from technical manuals for professional weavers online which left me more confused than enlightened, but your explanations and pictures of the finished fabrics brought it all together for me. Should any of my potential tartan choices not be available with a tartan selvedge, I now feel confident to discuss with my kilt maker how they address the issues created by these other types of selvedges.

Hi, Paul,

Thank you very much for your article. A kiltmaker classmate sent me your article, because I just started weaving my own tartan. Handweaving tartan does take a lot longer, but we’ve got better control over our selvedges, etc. One of the biggest challenges, no matter what the fiber, is each thread comes with its own thickness – even from the same mill! The unevenness in the selvedge should be taken care of at the mill at the time it’s fulled (washed). Obviously, some just don’t take the time because it’s so time consuming. It’s a pain! Hope all’s well there!