There is often a confusion about where tartan came from and what it actually means, ultimately it can be difficult to clear up the misunderstanding but perhaps the following thoughts might help.

Tartan , some common dictionary definitions

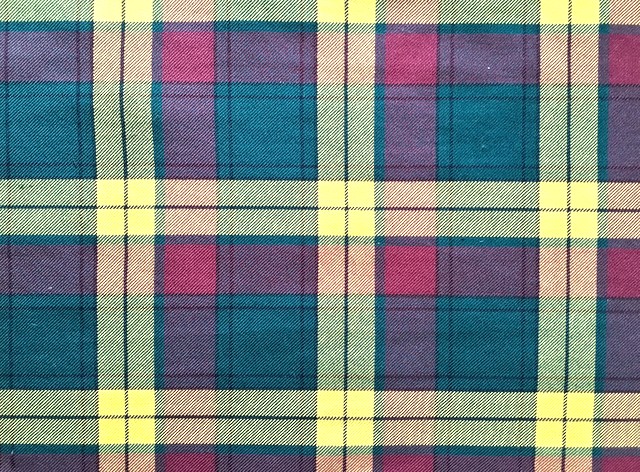

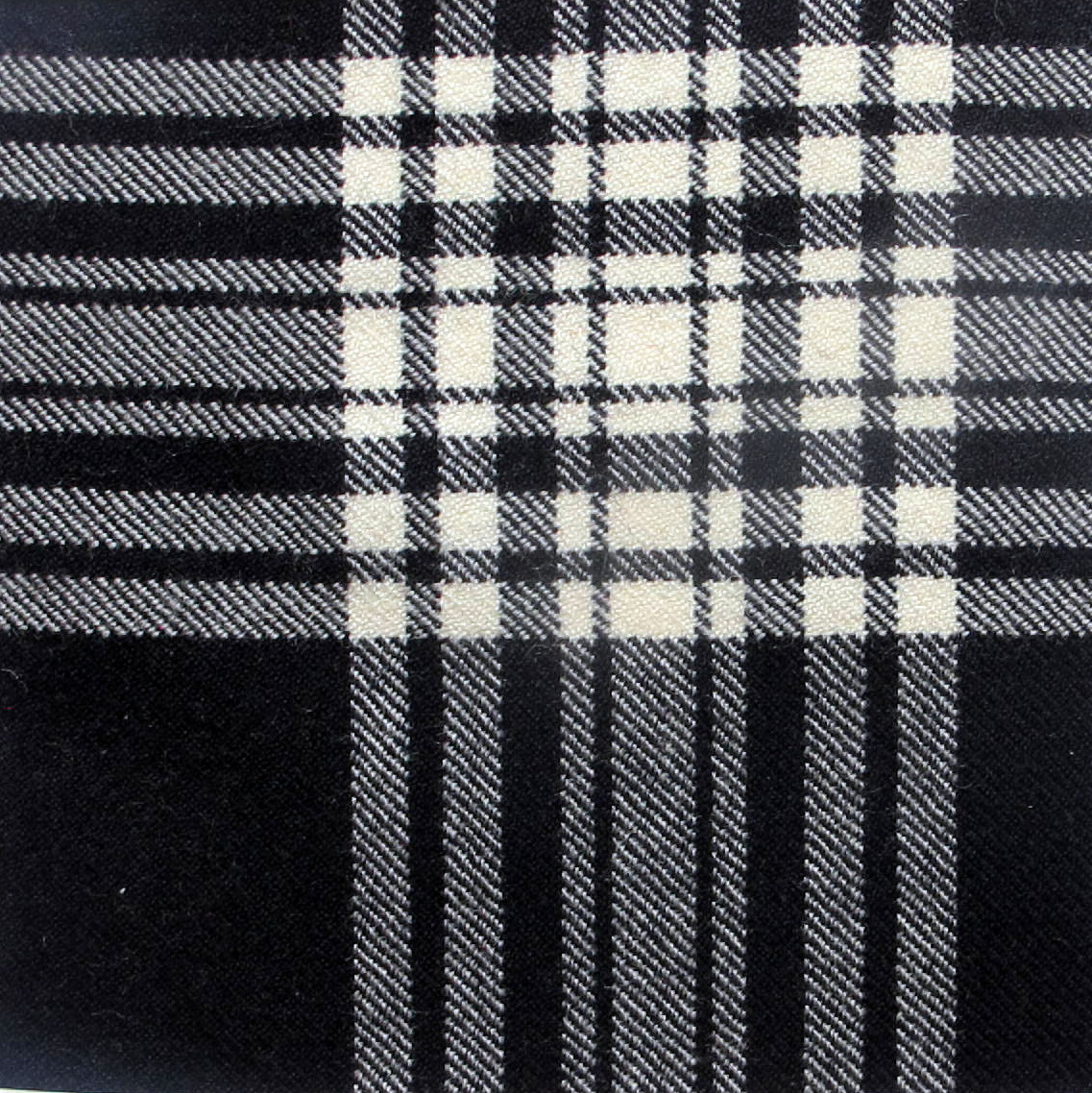

- a pattern of different coloured straight lines crossing each other at 90 degree angles, or a cloth with this pattern

- a pattern of squares and lines of different colors and widths that cross each other at an angle of 90°, used especially on cloth, and originally from Scotland

From the Scottish Register of Tartans

- Tartan (the design) is a pattern that comprises two or more different solid-coloured stripes that can be of similar but are usually of differing proportions that repeat in a defined sequence. The sequence of the warp colours (long-wise threads) is repeated in same order and size in the weft (cross-wise threads). The majority of such patterns (or setts) are symmetrical i.e. the pattern repeats in the same colour order and proportions in every direction from the two pivot points.

The word might have come from the Old French tiretaine ( c.1247) , meaning either a coarse mixed/union fabric of different warp and weft fibre or indeed a rich cloth, wool is often mentioned but it doesn’t appear that it was universal as linen or cotton was also utilised. There are even thoughts that it might have come from the City of Tyre or even brought in from Central Asia by the Tartars, both somewhat spurious…

Whatever the source it seems that it didn’t necessarily mean a patterned cloth, but more a long lasting or valuable one.

Woven cloth exists all over the world, anywhere that had fibre, of any sort, would have created fabric often with stripes, lines, and ultimately checks. Any woven cloth with a regular repeating series of threads of different colours in both the warp and weft would be considered as tartan. There are some examples of such cloth dating back over 3000 years found in Urumchi, China with other examples from findings in the historic Salt mines of Halstatt in Austria. These fabrics are remarkable survivors of a past age of very skilled weavers.

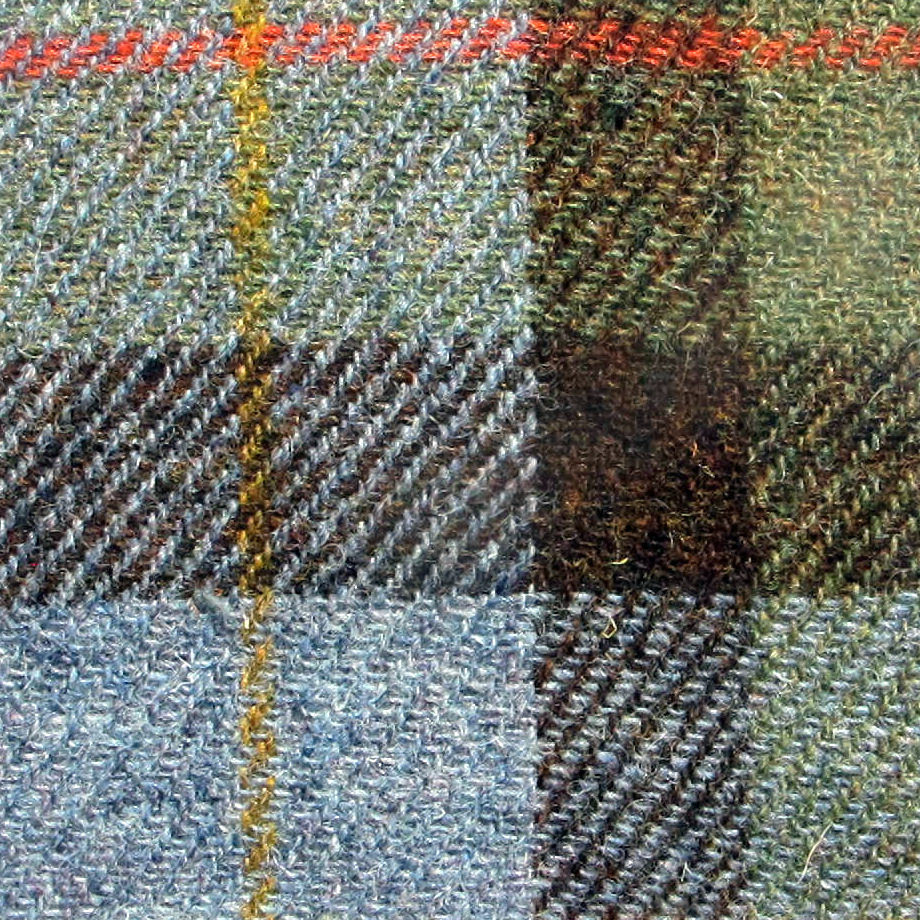

The first actual example of a tartan found in Britain is the Falkirk check, a very simple check in natural light and dark wools, dating to around 250AD. The most recently found example of an historic tartan from Glen Affric in the Highlands, has been confirmed to between 1500 -1600 is a very recognisable tartan design with multi pattern lines and 4 colours of dyed yarns. Scotland is generally the first place that tartan is identified with by most people and it has become the single most recognisable marker of the region.

In Scotland there is a well understood idea that different regions produced different tartan cloth, often from local dyestuffs, but the Highlands did have access to many imported raw materials from the mid 1500’s well before the craze for tartan happened. In 1815 the Highland Society of London asked the clan chiefs to submit samples of their clan tartans, but most really had no idea what their clan tartan was, but the enterprising weavers were only to happy to help and after 1822 King’s visit to Edinburgh the wearing of tartan took off, whilst once it was a Highland dress it became universally Scottish and weavers began to satisfy, indeed even create, the need for named or Clan tartans. One of the main weavers was William Wilson of Bannockburn who managed to almost create a taxonomy of tartan, and thanks to the wonderful archive left behind and still viewable that we know so much about the popularization of tartan.

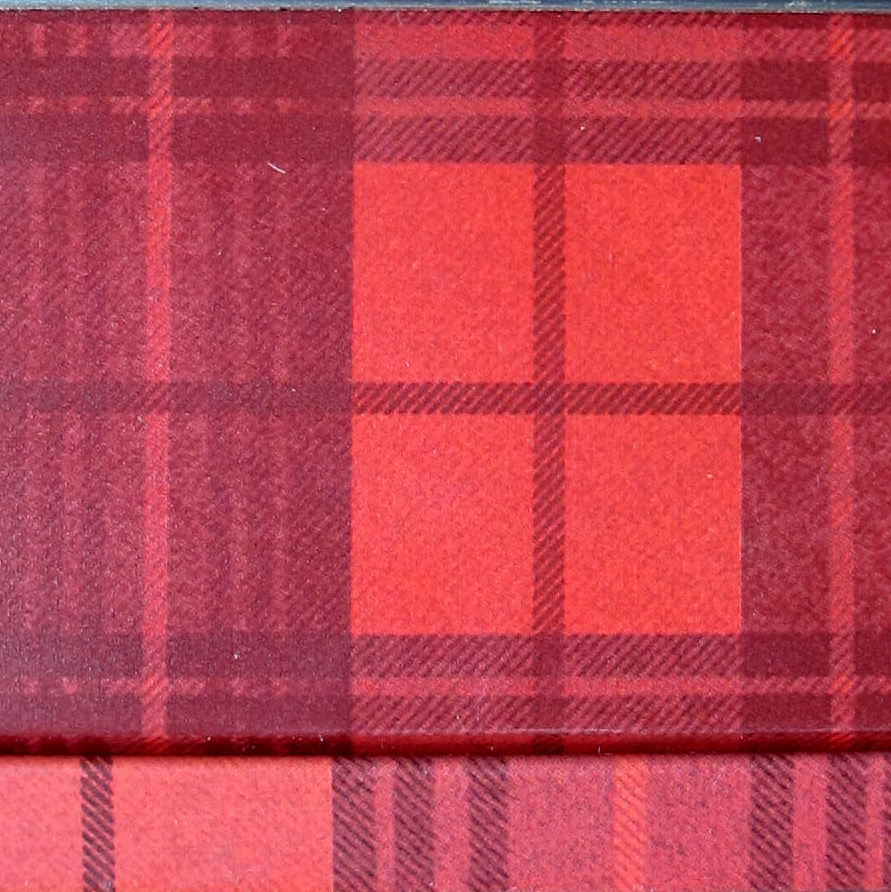

It is from this period that many of the Clan/named tartans were created and recognised. Then the colours were choosen largely by artistic desire without any great attachment as to meaning, today tartans are still being created but now often with symbolic meanings for the colours or number of threads.

Tartan is still very much alive and well, and wherever the Scottish have migrated across the world there now exists a very strong support for this iconic cloth.

Much is said about the constraints imposed on tartans, but in truth it is a design, usually woven with a twill, but it’s not essential, mainly woven in wool, mostly in a worsted yarn, but again not essential.

Over the centuries tartan has been created in wool, silk, cotton, and linen, and now appears as a synecdoche for Scotland or Scottish culture whether it is on fabric, paper, or metal.

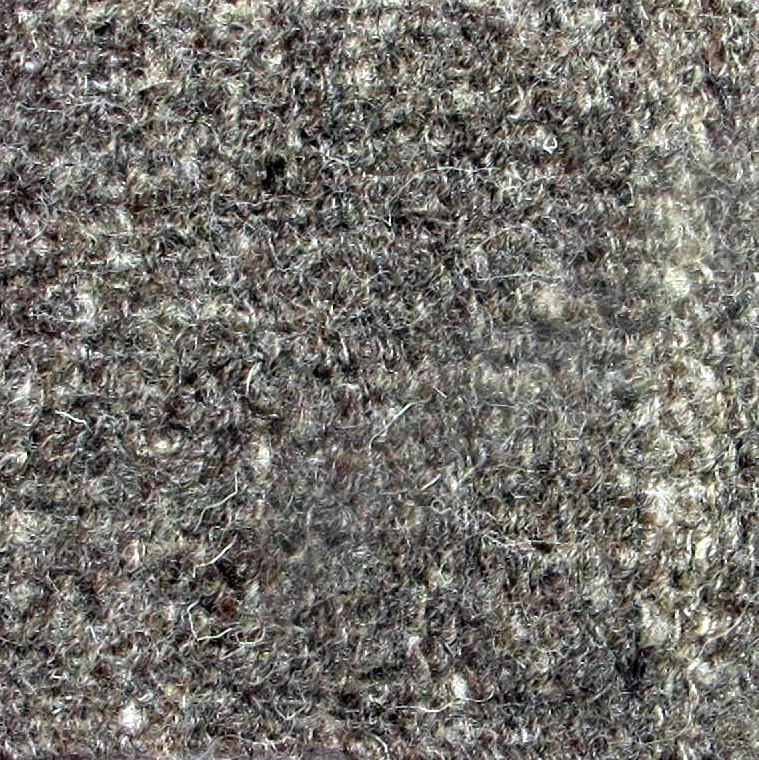

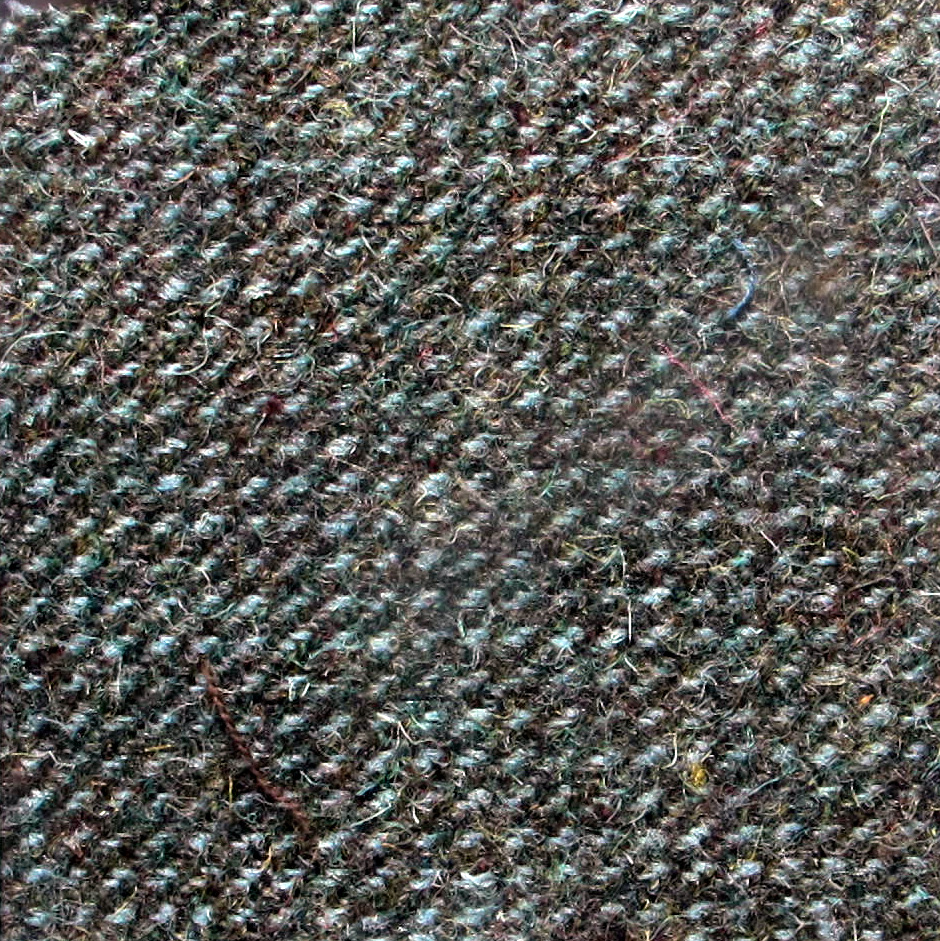

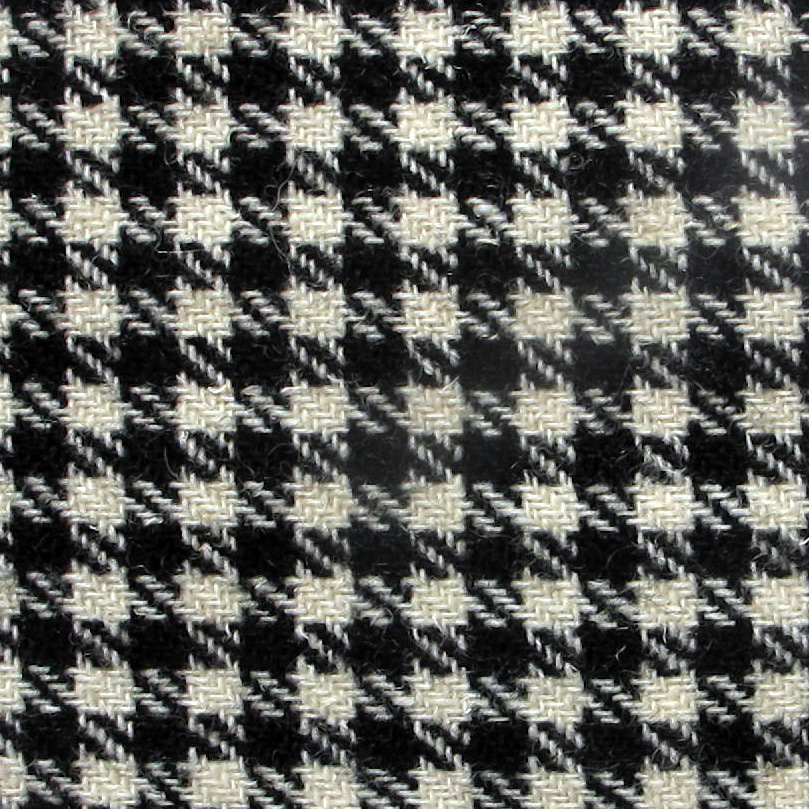

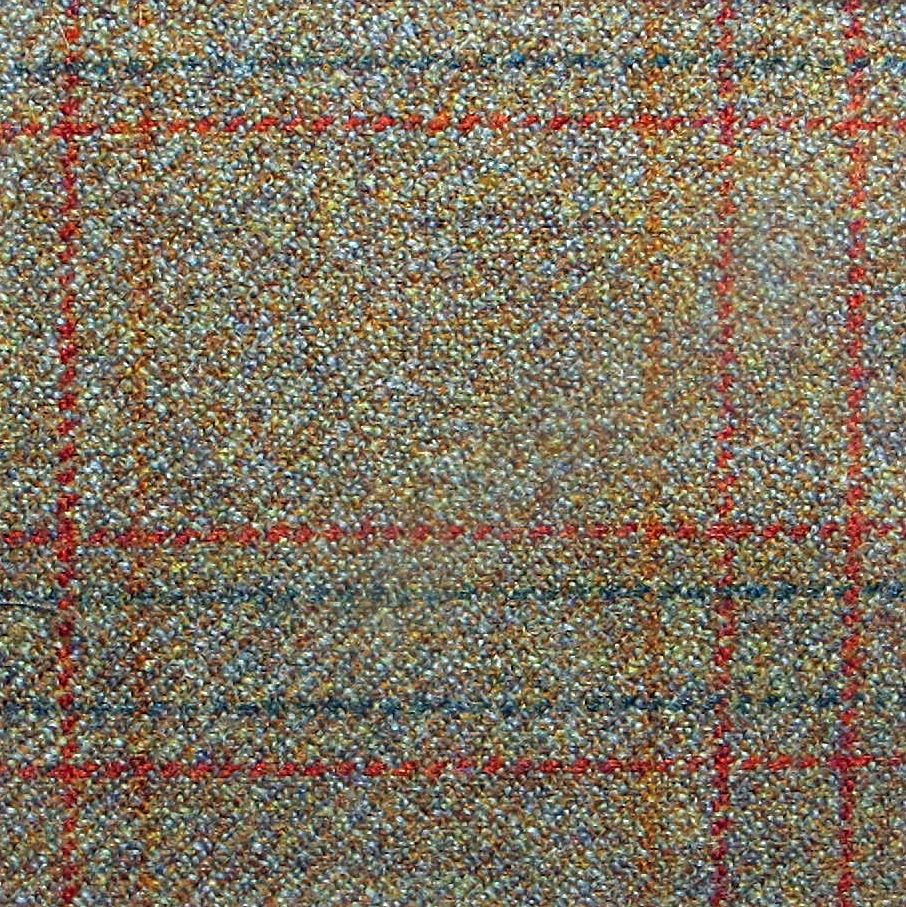

Examples of historical and tartan setts on wool and other substrates:

Notes:

Tweed: Often a slightly rough woollen cloth made with mixed coloured yarn, seen as country type clothing for outdoor use associated with Scotland and Ireland particulary but woven in many places.

The origin seems to have been a miss reading of the Scots word tweel meaning twill by a London merchant around 1830, by tweed, but the word gained a huge currency and fame.

Woollen yarn: a lighty spun yarn produced from randomly arranged fibres, often plied for knitting, but when woven produces a lofty fabric which is warm yet light. Often uses a general purpose fleece with shorter fibres.

Worsted yarn: a fine strong yarn produced from parallel fibres from long wool fleeces, mainly for weaving and produces a harder and smoother fabric used for prestige or luxury items

Plain or Tabby weave: a traditional weave of alternate or in and out threads on the weft and warp, the simplest weaving technique.

Twill weave: a type of weave with a distinctive diagonal rib, a hard wearing fabric, typically for tartan but also a characteristic of denim. Created by the weft going over one warp thread and missing the next two or three, and then offsetting on the next pass continuing to create the strong diagonal lines.