Often I am asked what is the difference between tartan and plaid, are they actually the same or what exactly are they? It’s quite a simple distinction, but can be rather involved depending on where you are in the world.

Tartan doesn’t have an absolute agreed definition but perhaps is best described as a pattern where there is a regular repeating arrangement of lines of colour at right angles creating a grid like design. Most of the time this refers to a woven cloth where the weft and the warp lines have the same formula, this is known as the thread count, and the repeating unit or square is called the sett. This grid like pattern often repeats as a mirror image giving a typical symmetrical and fairly usual tartan pattern. A few tartans are not symmetrical where the design block repeats by simply moving across. There are also a few tartans where the weft and warp are not the same, this is a little unusual but does happen especially with the fairly recent range of Welsh tartans, and a few rather early or historic tartans, perhaps by accident rather than plan!

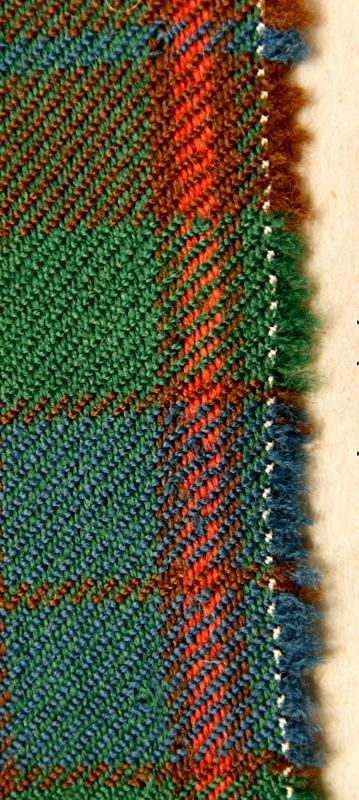

MacMillian Old in modern colours

Non symmetrical sett

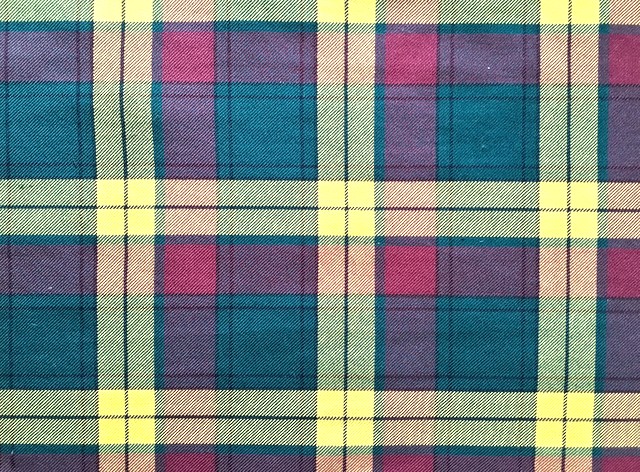

Buchanan in Antique colours

Symmetrical sett

It follows that even a simple 2 colour check conforms to this understanding although some feel that calling a simple check a “tartan” is a little excessive but the Shepherd or Northumberland Tartan is exactly that and MacGregor/Rob Roy is again a very simple 2 colour even square check – in the United States the same tartan in a larger check in red and black is frequently known as Buffalo Plaid and seen on cotton Flannel shirts . It is unusual to have more than 6 colours, and the repeating unit is often between 5″ – 8″, but there are several notable exceptions to this, often as bravura pieces, two extremes are pictured!

Shepherd or Northumberland Tartan

Sett size 1″ – 2 colours

Ogilvy Tartan

Sett size 23″- 7 colours

No one is entirely sure where the word “tartan” came, there are several theories, but examples of tartan have been found in archaeological sites around the world, notably in the Taklamakan Desert, Northern China, dating from 3000 years ago; well before Scotland had even been considered the birthplace of them and with little real basis for tartans there before the mid 1600’s.

Plaid is a Gaelic word meaning blanket, essentially a large wrap of cloth which in time became known as the Great kilt or Feileadh-mhor and then as the belted Plaid. This was made from 2 pieces of cloth roughly 4.5 yards long by about 28″ wide, joined together to create a large rectangle, this was wrapped around the wearer and became the standard garment, blanket, and sleeping bag.

It might well have been the most important item in the possession of a Highlander .The cloth was a simple woollen cloth woven by local weavers in colours of their choice, or whatever was available, doubtless it was mixed colours both of fleece and dye and over time, perhaps hundreds of years, local areas began to be known by what their weaver could produce and the origin of district or area tartans.

When Highlanders and Scots crossed the Atlantic to find new land and opportunities for various reasons, the word plaid was often misunderstood to mean the pattern of the blanket rather than the garment itself, and this is the root of the confusion.

In the UK the word plaid only normally means a large scarf or wrap usually worn by Pipers or traditional kilt wearers on special occasions, as a nod to the old fashioned or historic kilt attire. There are a few variations as well but often worn over one shoulder , either on the diagonal or perhaps folded square, and often it proves a valuable extra layer in the cold.

Traditional Fly plaid

Crossed Lairds Plaid

Traditional Lairds Plaid

In the US the word plaid usually means any sort of checked cloth, in any arrangement of lines or colours and the “tartan” word seems to be reserved for named, registered, or official tartans which conform to a regular repeating unit. There also seems to be quality difference that tartan is somehow “better” than plaid, and tartan is almost always wool and plaid can be anything from flannel cotton to quality merino wool.

So in essence a plaid is a garment and tartan is the cloth in the UK, and plaid a miscellaneous checked cloth and tartan is a regular repeat in the States, although Pipers still wear “a” plaid there!