I’ve been involved in a project in London Primary Schools, going in to talk, demonstrate and teach a little bit about drop spinning, using flax that they have grown and processed themselves. It’s part of an initiative by Cassie Liversidge ( http://growyourownplayground.com) to introduce school children to gardening, growing their own food and generally understanding a little about where food comes from. It’s a wonderful scheme, she has 8 schools under her wing and I think that everyone should look to supporting similar projects in every school.

It’s made me think about the process much more intently, having to work out the best way to cope with multiple groups of 6 or 7 children all wanting to learn at the same time , and indeed coping with dozens of sometimes random questions, and of course a little bit of crowd control as well. The key really was preparation , everything was ready and a few ideas in reserve if things didn’t go quite to plan. I was also giving a very quick potted history of spinning from the beginning until now, the small potato on a stick certainly worked well, but of course time and concentration span was short.

I had spun flax before, but it had never had as much attraction for me as wool, but it was something that I wanted to add to the armoury, and has certainly proved useful not least in spinning my own bookbinding threads. However spinning the line flax proved another challenge, and actually I think I might even have a not so secret fondness for it now.

For those who are a little uncertain about the way that flax is grown and processed read on, for others you can skip quite a bit.

Flax is an incredibly old crop, evidence has been found of cultivation and use for over 30,000 years, from Russia it spread across all of Northern Europe and to India and China. Growing, it generally prefers slightly cooler climates with reasonable rainfall. In Ancient Egypt most of the prestige cloth was linen and was specially chosen for the elite and the pure. It was very well regarded by the Romans and throughout the Middle Ages was one of the most hard wearing fabrics available. It was the Low Countries that became very well known for the growing and production of flax and in time North America also took to the crop. However once cotton growing and production in the 1800’s became widespread the use of linen decreased and by the twentieth century it had a considerably smaller market share. Today there are still some small scale flax growers but most of the raw flax now comes from Russia. Flax can grow to about 3′-4′ high and the flowers are a wonderful pale blue, it has a strong single stem which is the essential part of the plant. Harvested at about 3 -4 months after planting, usually when the seeds are setting, by pulling the entire plant rather than cutting in order not to lose any precious fibre. Leaving the plants to grow for longer causes the fibre to be coarser, but still useful.

The stems are allowed to dry for a few weeks and then the seeds removed using a metal comb or rake ( rippling) and saved either for replanting or for use as food stuff or linseed oil

The stems are then rotted (retted) to help expose the bast fibre,this process normally takes a few weeks and works as bacteria breaks down the outer stem. There are several ways of doing this , but usually the bundles are left in a pond or a large tub of water, or on wet grass to dew rett, either way the process is very similar.

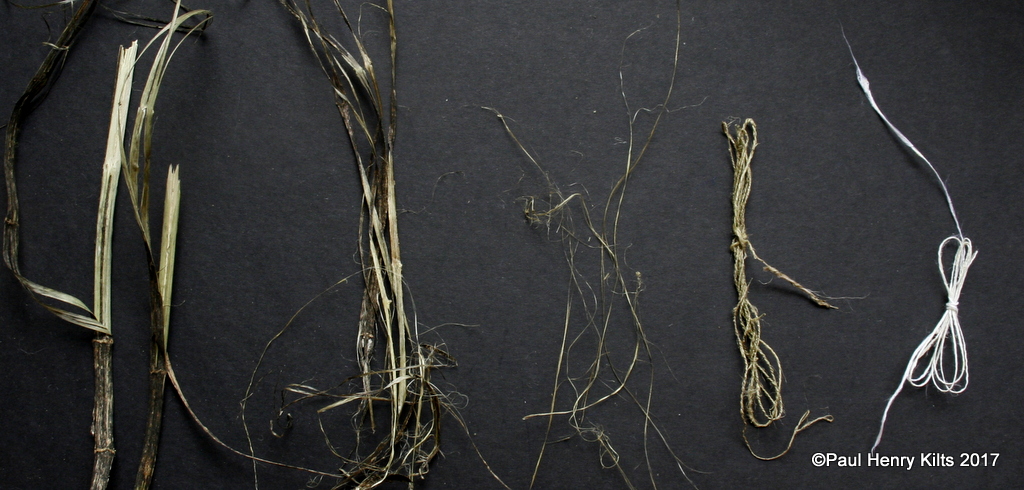

Once the stems are completely dry, after days, weeks, or longer the stems are then broken by squashing, hammering, or actually breaking and bending the stem (scutching) and the inner fibre is then exposed, the broken stem and core bits (boon) are waste and the precious fibre (line) is kept long and straight.

The retted stems look rather dirty and useless , but when broken and the bast fibre is revealed all the hard work seems worth while.

The retted stems look rather dirty and useless , but when broken and the bast fibre is revealed all the hard work seems worth while.

The fibres are then combed (hackled) to even out all the fibre and to help to remove shorter lengths (tow), which can be re used to make slightly less perfect yarn, but perfect for coarse cloth or ropes.

The newly combed hank has a look of horsehair about it, depending on the retting method it can be grey or golden, indeed flaxen hair is a very appropriate description.

Harvesting the fibre takes a long time and it is hard, messy, and dusty work, it was however fascinating to watch the children working together as teams to obtain as much fibre as they did.

There is always a lot of wastage,about half the weight of the stalk infact, although this can be picked through a second time and the shorter fibres rescued and used as second best fibre and the remains can still serve as animal bedding, as a mulch, or just to add to the compost heap.

Now comes the ultimate task, the actual spinning, the bit which I think the pupils found the most demanding. I choose a simple wooden top whorl as I find that is the easiest way to learn to spin, but there is an important sequence to learn.

Making sure that everyone knew their left from right, and which way was clockwise took a few moments, and they did need reminding, and generally with embarrassed good humour. It was important to me that they could see that spinning was an interesting and fun thing to try, although each session was all about learning, there is a greater chance that some of the information will stick if it is enjoyable.

Some of the children did actually seem to “get” the idea, and if I had had a longer session with them I’m sure that many would have proved very successful. A drop spindle is perhaps one the simplest and oldest fibre tools and yet capable of creating fine and coarse threads, they are cheap to make or buy and they can have an indefinite life, they need virtually no maintenance, and seldom go wrong, it is the spinner who controls the tool, not the other way around.

Some of the children did actually seem to “get” the idea, and if I had had a longer session with them I’m sure that many would have proved very successful. A drop spindle is perhaps one the simplest and oldest fibre tools and yet capable of creating fine and coarse threads, they are cheap to make or buy and they can have an indefinite life, they need virtually no maintenance, and seldom go wrong, it is the spinner who controls the tool, not the other way around.

It was wonderful to watch their faces when the soft fibres were turned into fairly hard and strong string like yarn, mouths dropped open in amazement part of the magic that still fascinates me, watching the twist rise up from the drop spindle. Spindles fell many times, breaks in the yarn were mended, but most of them persevered and they did actually create some linen yarn, and the challenge of turning flax in linen was almost completed.

It was wonderful to watch their faces when the soft fibres were turned into fairly hard and strong string like yarn, mouths dropped open in amazement part of the magic that still fascinates me, watching the twist rise up from the drop spindle. Spindles fell many times, breaks in the yarn were mended, but most of them persevered and they did actually create some linen yarn, and the challenge of turning flax in linen was almost completed.

Of course they didn’t produce huge quantities of yarn , but I added to the school production and then plied two strands together to make a stronger and more even yarn.

Once spun the yarn needed to be finished, this meant boiling for an hour with a little washing soda, which served to set the twist, remove grease and dirt and soften the yarn, also it did make the yarn a lot lighter in colour as well.

Once spun the yarn needed to be finished, this meant boiling for an hour with a little washing soda, which served to set the twist, remove grease and dirt and soften the yarn, also it did make the yarn a lot lighter in colour as well.

Ultimately the goal was to produce enough yarn from each school to be able to knit a little jumper to display in the school corridors, so with all the extra lumps and bumps in the yarn the children now have something very real to admire, that they have largely been responsible for making.

The whole project has been a wonderful experience, tiring and demanding, but I’d do it all next year I hope!

The retted stems look rather dirty and useless , but when broken and the bast fibre is revealed all the hard work seems worth while.

The retted stems look rather dirty and useless , but when broken and the bast fibre is revealed all the hard work seems worth while.

Some of the children did actually seem to “get” the idea, and if I had had a longer session with them I’m sure that many would have proved very successful. A drop spindle is perhaps one the simplest and oldest fibre tools and yet capable of creating fine and coarse threads, they are cheap to make or buy and they can have an indefinite life, they need virtually no maintenance, and seldom go wrong, it is the spinner who controls the tool, not the other way around.

Some of the children did actually seem to “get” the idea, and if I had had a longer session with them I’m sure that many would have proved very successful. A drop spindle is perhaps one the simplest and oldest fibre tools and yet capable of creating fine and coarse threads, they are cheap to make or buy and they can have an indefinite life, they need virtually no maintenance, and seldom go wrong, it is the spinner who controls the tool, not the other way around. It was wonderful to watch their faces when the soft fibres were turned into fairly hard and strong string like yarn, mouths dropped open in amazement part of the magic that still fascinates me, watching the twist rise up from the drop spindle. Spindles fell many times, breaks in the yarn were mended, but most of them persevered and they did actually create some linen yarn, and the challenge of turning flax in linen was almost completed.

It was wonderful to watch their faces when the soft fibres were turned into fairly hard and strong string like yarn, mouths dropped open in amazement part of the magic that still fascinates me, watching the twist rise up from the drop spindle. Spindles fell many times, breaks in the yarn were mended, but most of them persevered and they did actually create some linen yarn, and the challenge of turning flax in linen was almost completed.

Once spun the yarn needed to be finished, this meant boiling for an hour with a little washing soda, which served to set the twist, remove grease and dirt and soften the yarn, also it did make the yarn a lot lighter in colour as well.

Once spun the yarn needed to be finished, this meant boiling for an hour with a little washing soda, which served to set the twist, remove grease and dirt and soften the yarn, also it did make the yarn a lot lighter in colour as well.